A New York Post article about an unsafe “pizza joint manager” — who was reported to have sparked hepatitis C scare — made a few rounds on the panicked social media circuit earlier this year. The Post alleged that the Indiana restaurant worker, who is infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), was busted for heroin use on the job. The restaurant was sanitized following the arresting officer’s report that the worker was handling food without using necessary health precautions to cover her open sores. The health concern over the issue is more than warranted, given a 2017 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) linking the growing heroin epidemic and the increase in HCV infection.

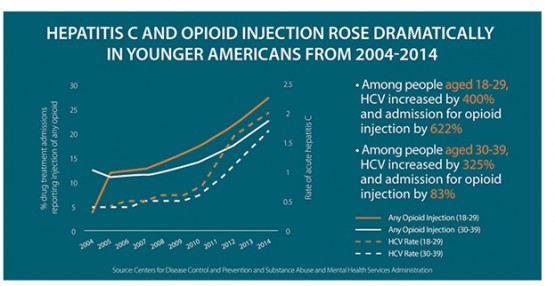

The CDC’s May 2017 report detailed startling coincidences between the rise of hepatitis C cases and America’s heroin epidemic. According to the report, from 2010 to 2015, the documented number of HCV cases of infection increased by 294 percent. The report noted that the rates are highest among people who’ve injected drugs. In a more recent report released in December 2017, the CDC noted that across the United States, there are serious, concurrent increases in admissions for opioid injections and acute hepatitis C infection from 2004 to 2014; 93 percent for opioid-related hospital admissions; and 133 percent for HCV infections.

HCV transmission

Hepatitis C is a highly contagious viral hepatitis that can be easily spread through contact with a contaminated person’s body fluid. This means that the virus can be spread through sex, childbirth (mother to child), as well as injection drug use (IDU) — which is the most common risk factor for infection according to the CDC. This helps explain why people who inject drugs (PWID) are at extreme risk for HCV infection.

The majority of people with acute HCV infection do not show signs or suffer the symptoms of the infection. In cases where symptoms manifest, they appear two to six months after exposure and transmission. HCV infection symptoms include a flu-like illness accompanied by fatigue, muscle pains, stomach pain, jaundice, fever, and poor appetite. Because in many cases, HCV symptoms don’t manifest, acute HCV infection silently develops into chronic infection.

It is not uncommon to have the infection for 15 years or longer, before being diagnosed. This leaves a long period of time for an undiagnosed person to unknowingly spread the disease through the sharing of needles.

What the CDC reports state:

- Incidence of hepatitis C infections have been steadily rising since 2010 to 2015

- In 2014 alone, 30,500 new cases of HCV infection was reported; 16,500 new cases were documented in 2011

- The most dramatic increase of HCV infections was seen among younger Americans aged 18 to 39, from 2004 to 2014. Specifically, in translation: a 400 percent increase in HCV infection in this age group; an 817 percent increase in admissions related to injections of prescription opioid; a 600 percent increase admissions for injections related to heroin use.

In summary, there is very reliable evidence that the heroin epidemic and opioid crisis has increased the incidence of HCV’s growing spread. This is a serious public health concern.

The CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention Director, Jonathan Mermin, warned the public that “Hepatitis C is a deadly, common, and often invisible result of America’s opioid crisis.”

“By testing people who inject drugs for hepatitis C infection, treating those who test positive, and preventing new transmissions, we can mitigate some of the effects of the nation’s devastating opioid crisis and save lives,” Mermin added.

ADRLF encourages you to pay close attention to this growing two-fold crisis, through vigilant awareness, prevention, and treatment — and by helping us to convey this important message to your communities, near and far; particularly the youth.

To learn more about the CDC report, check out these resources:

- Increase in hepatitis C infections linked to worsening opioid crisis

- Viral Hepatitis

- Article for the Hepatitis Awareness Month in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

To learn more about hepatitis C, read on: